Camille

If only I could see a landscape as it is when I am not there.

But when I am in any place I disturb the silence of heaven

by the beating of my heart.

Simone Weil

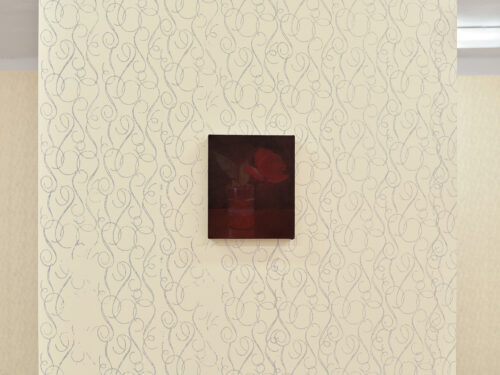

In her essay On Style, Susan Sontag argues that art is “a thing in the world, not just a text or commentary on the world.”1 Encountered as art, a work is “an experience, not a statement or an answer to a question.”2 Sontag defines the autonomy of art as “its freedom to ‘mean’ nothing,”3 without precluding consideration of its function or capacity for social impact. What mediates between the work and its audience is the exhibition space. Ant Łakomsk, together with Zuzanna Kozłowska, create circumstances in which visitors are folded into the arrangement of paintings and objects installed in the space, so that the whole situation takes on the character of a covert happening—the viewers stage the act of looking at the painting. If all the elements of the exhibition are treated as props, the arranged environment poses a dialectical question—what becomes more important in the situation at hand: the surface of the work being viewed, or the relation between viewer and work? Ant Łakomsk touches only the surface of a vast reservoir of associations, incorporating fragments of it into her own works. Her borrowings, however, are closer to linguistic and semantic paraphrase than to visual methods of appropriation.

The references she draws on are often hazy, mediated by digital reproductions. The artist attempts to translate originals displayed on a phone or computer screen back into analog techniques, while simultaneously blurring the legibility of the reference. She builds connections by combining figures, spaces, and props as well as diverse painting techniques. She fuses lyrical figuration with abstract passages that take the form of graffiti, wallpaper motifs, or smoke filling the frame of the canvas. The composition achieved through the juxtaposition of quotations resembles a literary montage.

Isabelle Graw’s approach helps to structure this logic of montage and blurred reference. She proposes reading painting through the prism of Charles S. Peirce’s semiotic theory of indexicality.4 In addition to highlighting the inextricable bond between the artist and their work, she sets out the function of the index, which directs the viewer beyond the space of the image. The index—understood by Peirce as a sign connected to its object by contiguity or causation—points beyond the image to its sources (gesture, body, the time of the event), directing attention to what lies outside the frame. This mechanism is evident in Łakomsk’s compositions, which often hinge on fragmentary misalignment. As a result, they evoke the spectral presence of multiple authors.5 This kind of multiplication of the self—its insertion into a historical conglomerate—activates the ritual (sacred or secular) mode of being with the work of art that Walter Benjamin associated with its cult value.6

When I look at Łakomsk’s Leisure, I think of Gwen John’s A Lady Reading (1910–1911). In John’s painting, the scene unfolds in her Paris apartment—a setting she returned to repeatedly. John painted two versions of the painting—in the first, the depicted figure’s features were modeled on the Virgin Mary as depicted in Albrecht Dürer’s woodcut Annunciation from the Life of the Virgin series, whereas in the later 1911 iteration the figure bears the artist’s own face.7 Duplication does not, however, function as a supplement to self-representation—the artist treats the figures, regardless of any resemblance to her own likeness, as vessels that become spaces for dialogue with the legacy of earlier generations of painters. The essence of both of John’s paintings is less the capture of any autobiographical truth than the record of the formation of her artistic identity.8

Ant Łakomsk evinces similar aims, immortalizing figures in her paintings. These are flashes and glimmers in the form of laconic portraits, depicting subjects suspended within claustrophobic compositions. The artist depicts figures at a moment of a certain absence, a detachment from the body—as they think, read, or dream distant worlds. The figures in the paintings are phantoms that embody references to art history.

The distancing of the paintings, the distillation of them from autobiographical content, and finally the attempt to efface the self in favor of another subject call to mind the process of decreation, which is difficult to define unequivocally. If it must be put in a single sentence, it simply means “to dislodge” the self “from the centre” or “to undo the creature in us.”9 The term becomes a connective tissue for Anne Carson, who in her cross-genre work brings together the spiritual and mystical experiences of three figures, as articulated in their writing: Sappho, Marguerite Porete, and Simone Weil—who coined the notion of “decreation.” Carson guides the reader through the essay by layering temporalities and quotations—accumulating them to speak of the erasure of the self and of an ecstasy that exceeds words. The method of building a literary universe out of excerpts and borrowings “forces the perceiver to a point where she has to disappear from herself in order to look”10; to paraphrase Carson: it forces the painter to disappear from herself in order to paint. By modifying and incorporating existing narrative patterns, Łakomsk touches on this specific vision, even though the protagonists of her works may suggest a certain self-referentiality. The paintings depict a person who, paradoxically, experiences the fading of the self.

Stepping beyond her own practice, the artist goes a step further—using elements of Marc Camille Chaimowicz’s (1947–2024) practice as a matrix for her exhibition. A reference to his legacy is already present in the title. His practice encompassed installations, paintings, works on paper, photographs, books, and intimate performances and happenings in public space. Chaimowicz negotiated, in his work, the boundaries between fine art and craft, and between the public and the private. He addressed questions of identity, memory, and time. His distinctive artistic stance was marked by dandyish nonchalance. Within it, he developed cohesive aesthetics; designed fabrics and wallpapers and translated them into drawings; made paintings and spatial works; refitted gallery and museum interiors to resemble his studio-apartment; combined camp with refined craftsmanship; and, in his very posture, contested the monolithic character of identity and subjectivity.

Marc Camille Chaimowicz regarded his practice not as a method but as a comprehensive project in which metaphor and poetics serve emancipation. In his 1987 text On the Dialectic Between Fine Arts and Design, which can be read as a kind of manifesto, the artist set out to explain the meanings of bringing fine art and craft together in his own work. It is worth noting that Chaimowicz employs a brief set of instructions not to underscore formal or historical differences between these two forms of art, but to elucidate—through them—the fluctuations of his subjectivity. He explains that the core of his practice is a search for the self, and that craft and the poetics of design enable a passage from selfhood toward namelessness and anonymity. Describing the transformative potential he sees in his practice, he writes: “A fire extinguisher, a coffee pot, an armchair or a jug are each inbued with instant meaning… They tell us what they are, and what they do… in a way that the mute, enigmatic painting does not. Design gives us answers, Fine Art poses questions. We take meaning from Design… and give meaning to Fine Art.”11 Chaimowicz’s transgressive multiplicity is not only an accumulation of forms, techniques, and objects, but also a framing of their relations as a territory for seeking the limits of the self—as subject and as artist. In dedicating this exhibition to Chaimowicz and engaging his practice, Ant Łakomsk pursues kindred explorations of art’s capacities and agency.

Franciszek Smoręda (Translated by Martyna Miernecka)

______________

- 1 Susan Sontag, „On Style,” in Against interpretation: and other essays (New York: Dell Pub. Co., 1966), 21.

2 Sontag, “On Style,” 21.

3 Sontag, “On Style,” 23.

4 Isabelle Graw, “The Value of Liveliness,” in Painting beyond Itself: The Medium in the Post-medium Condition, ed. Isabelle Graw and Ewa Lajer-Burcharth (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2016), 91–92.

5 Graw, “The Value of Liveliness,” 91–92.

6 Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 1968), 218–25, https://esquerdadireitaesquerda.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/benjamin-illuminations.pdf.

7 The first version of the work is in the collection of Tate in London (Gwen John, A Lady Reading, 1910–1911, oil on canvas, 40.3 × 25.4 cm), while the second version belongs to the collection of MoMA in New York (Gwen John, Girl Reading at a Window, 1911, oil on canvas, 40.9 × 25.3 cm).

8 Maria Tamboukou, Nomadic Narratives, Visual Forces: Gwen John’s Letters and Paintings (New York: Peter Lang, 2010), 51–56.

9 Anne Carson, Decreation. Poetry, Essay, Opera (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 165, 167.

10 Carson, Decreation, 169.

11 Marc Camille Chaimowicz, “On the Dialectic Between Fine Arts and Design,” in Marc Camille Chaimowicz: Writings and Interviews, ed. Anne Vaillant (London: Sternberg Press, 2025), 565.

Photos by Bartosz Zalewski. Courtesy Turnus, Warsaw